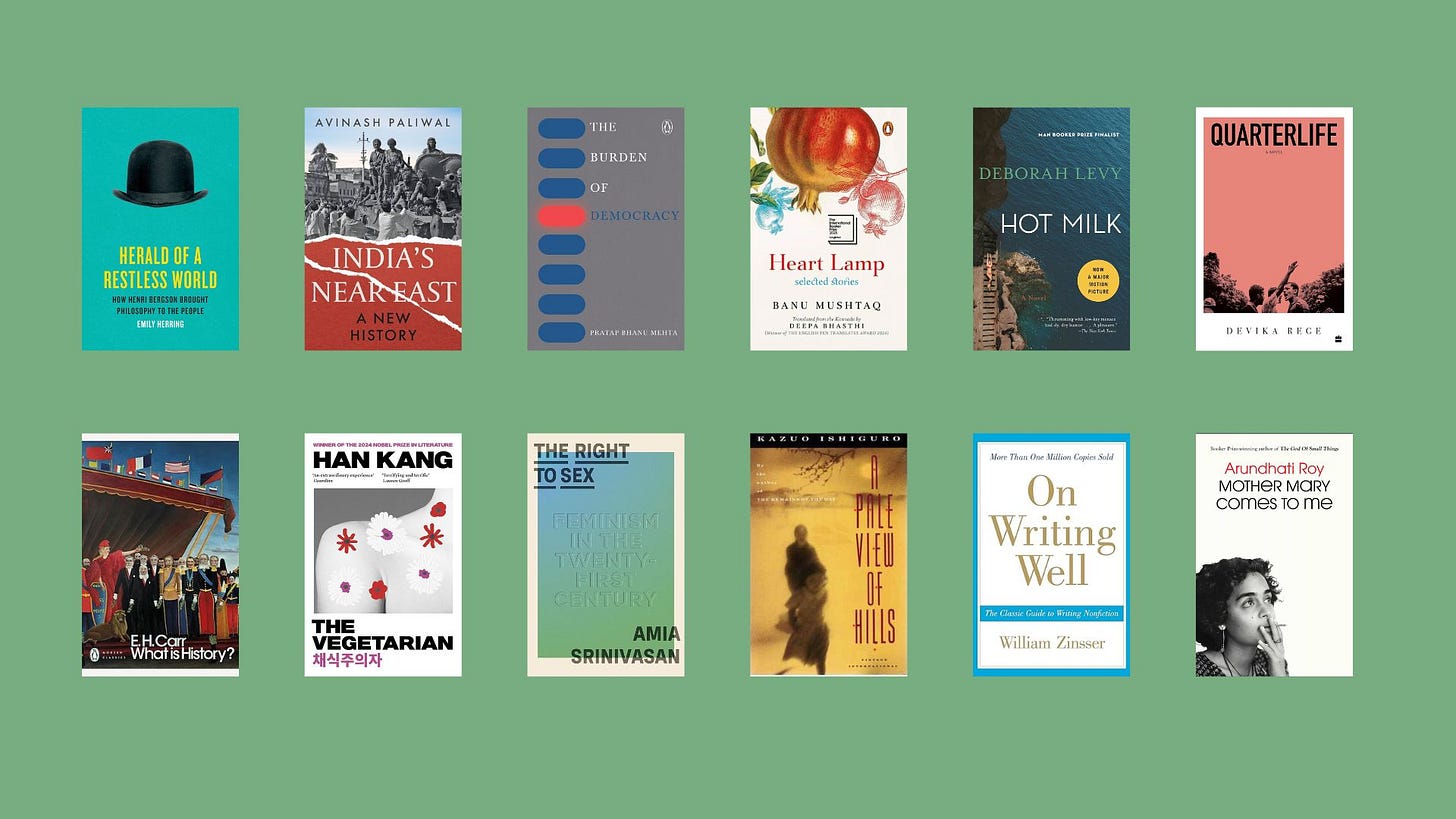

books I read in 2025

a wrap-up of reading, writing, and PhD

Dearest gentle reader,

It is that time of the year again, when, like several others I see on Substack, I take stock of the books I read in 2025. (Here is a link to check the books and movies I watched in 2024.)

2026 is upon us. And like how. The world seems to have gone mad. As it turned out, 2025 was already a challenging year. 2024, before that. And 2023. And 2022. And COVID-19 before that.

Come 2026, and Trump, the US leader, has already struck Venezuela, gotten hold of the dictator, Nicolas Maduro, and brought him to the United States on the pretext of involvement with drug supply. But, as Trump himself has made it clear, it is all about oil. With Venezuela out of the way, Trump’s focus has already shifted towards Greenland, which is an autonomous territory of Denmark.

Besides that, the Russian war in Ukraine continues to rage on. Genocide in Gaza continues, albeit with a brief hiatus. Against this backdrop of geopolitical turmoil, there is also an onslaught of AI capitalism. AI companies are out to transform our world almost entirely, both literally and metaphorically.

Witnessing such socio-political upheavals and transformations, and pursuing a PhD simultaneously, is a considerable amount of work. In such circumstances, even as the world begins to fall apart, one brick at a time, I take refuge in books.

I started 2025 reading Emily Herring’s Herald of a Restless World, a book about the life, times, and philosophy of Henry Bergson. Sometime in the mid-1910s, when a woman walked up to him after his class and asked him what his philosophy was, Bergson replied: “I simply argue, Madam, that time is not space”. What did it mean? When philosophers theorised time, they treated it as something stable—frozen in symbolic representations of a clock, calendar, or the points on the graph. Bergson’s conceptualisation of durée refutes this. I write about the book as follows:

Herring tells Bergson’s story with sheer brilliance. In tracing his life, Herring creatively draws on the lives and stories of people around him to portray the life of the philosopher. By opening each chapter with engaging anecdotes about Bergson, Herring places him in the limelight and foreshadows him, just as his conception of durée would inform us about time. By doing so, Herring brings Bergson—the man and the philosopher—to the people.

Click here to read the full review of Emily Herring’s Herald of a Restless World.

After a brief stint with philosophy, I read Avinash Paliwal’s India’s Near East: A New History, a book on India’s relationship with countries connected—and sharing borders—with India’s northeastern provinces, such as Bangladesh and Myanmar. Paliwal’s book shows how domestic interests came to interact with foreign policy interests in India’s policy towards the near east, promoting democracy, bolstering autocrats, arming rebels, waging wars, building ports, and granting loans.

About the book, I wrote: ‘Paliwal’s book is an important correction to the omission of the historical study of India’s near east. Paliwal convinces the readers that the history of India’s near east is worth reading, pausing, and introspecting on.’ Click here to read a review of Paliwal’s book.

In April, when I travelled to India to conduct my PhD fieldwork, and while relaxing at home, I read Pratap B Mehta’s The Burden of Democracy. Mehta’s 2003 book is a provocative essay on India’s democracy. One of the most evocative things Mehta wrote was that India never had ‘unity in diversity’, unlike the general understanding, but what India had for a very long time was that Indians were ‘diverse in their unities’, which enabled ‘each of us to imagine the connection with the others in his/her own way’. Check out my review of Mehta’s book on democracy here.

Next, I picked up Banu Mushtaq’s Heart Lamp. I wish I had read this book in Kannada, a language in which it was first published. Each story in the “Heart Lamp” opens up the life of a Muslim woman. The reader encounters that beneath all their sensible and sartorial characteristics, there is a story of suffering, stigma, patience, and perseverance. Mushtaq’s stories are are vivid, eloquent, illustrative, and at times, witty. To read the review of Mushtaq’s Booker-winning Heart Lamp, click here.

I then read one of Ashis Nandy’s essays on the politics of Gandhi’s assassination. Nandy is an astute observer of the human psyche. In his essay, “Final Encounter: The Politics of the Assassination of Gandhi”, published in 1980, Nandy argues that Gandhian thought and ideas posed a threat to the traditional society that persisted in India. Nandy suggests that Gandhi was ‘neither a conservative nor a progressive’: neither did he seek to preserve the past nor to protect the new. To read the notes on Nandy’s essay, click on the link here.

In August, I read Devika Rege’s Quarterlife, published in 2023, which explores the fraught political realities in India after the emergence of the right-wing nationalist party, which rose to power in 2014. The story follows three people whose lives are deeply intertwined with each other and those around them. Set in Maharashtra — where business capital and Maratha identity collide and shape political tensions — the novel also traces how Hindu nationalist ideologies first took root and came to sustain. About the book, I wrote: ‘Devika Rege’s Quarterlife serves as an ode to the deeply contested political realities in Modi’s India’. To read the review, click here.

In September, I read E.H. Carr’s seminal work What is History?, which discussed and debated history and historical theories of his time. Carr writes at one place: the ‘historian collects [facts], takes them home, and cooks and serves them in whatever style appeals to [them]’, but facts, themselves do not tell anything, they only make sense when the historian calls on them. In that sense, all history is selective, and objective history is a ‘preposterous fallacy’. Check out the notes on E.H. Carr’s book on history here.

I also read Han Kang’s The Vegetarian in September. The book begins as follows: ‘Before my wife turned vegetarian, I had always thought of her as completely unremarkable in every way’. And I was hooked on this book throughout. I wrote:

The Vegetarian by Han Kang is a novel that defies all forms of social taboos. In doing so, Han Kang’s novel easily complicates and tackles social realities, expectations, and choices, opening us up to a new future. No doubt the story is bleak and gloomy. There are also things that cause so much discomfort as one reads them. But for what it is worth, The Vegetarian is too brilliant.

Read the full review of Han Kang’s The Vegetarian at this link.

In October, I returned to Brisbane from a long and arduous few months of research and writing in Delhi and India. It was also the time for me to pick up some philosophy. And who better than Amia Srinivasan, a feminist philosopher, who wrote The Right to Sex. In the book, Srinivasan asks: Are men entitled to sex? Srinivasan says: No. In fact, ‘there is no right to sex’, and ‘to think otherwise is to think like a rapist’ (p. 95). Sex is not a sandwich. It cannot be distributed in society. Just like a sandwich, which every child might get in your class, except for you, because of your race or whatever, the distributive nature of sex is itself problematic. What Srinivasan does in The Right to Sex is to turn feminism on its head and ask uncomfortable questions that, even when they animate our present world, are difficult to answer. Click on this link to read the review of the Right to Sex.

Towards the end of October, I read Kazuo Ishiguro’s A Pale View of Hills. It is a story narrated by Etsuko, a Japanese woman who had moved to rural England with her second husband. The story begins with an unexpected visit from her daughter, Niki. And in the next few pages, there is a sense of confusion: Niki’s elder sister, Keiko, had died by suicide years earlier in Manchester, and Niki did not go to her funeral. Treat this as a hook. I wanted to know so much about why she would die, what happened to her, and how Etsuko ended up with a second husband. Read the full review at this link.

In November, I read Deborah Levy’s Hot Milk. Deborah Levy’s 2016 Booker shortlisted novel Hot Milk is about Sofia Papastergiadis, a 25-or-so-year-old anthropologist-cum-barista, and her mother Rose, who travel to Almeria in Spain to attend a clinic in search of a diagnosis and treatment for Rose’s mysterious paralysis of her legs. I really loved this book. About the book I wrote, ‘Deborah Levy’s writing is enviable in its elegance. Just as a Medusa sting, whose physical pain Sofia came to empathise with when compared to Ingrid’s behaviour, Hot Milk is unsettling even as you finish reading the last sentence.’ Click here to read the full review of Deborah Levy’s Hot Milk.

In December, I read Arundhati Roy’s Mother Mary Comes to Me. In the essay where I reviewed her book, I pointed out the deeply troubled relationship I have had with Roy. Growing up in Sainik School, during the early years of my schooling, I was administered a steady dose of nationalism, and Roy-like characters were the real internal enemies that supposedly destabilised the Indian nation. And from there, towards my admiration for Roy, it’s been some journey. In Mother Mary Comes to Me, Arundhati Roy steers the flow of rage, defiance, sorrow, joy, and love in the correct portion. Just like her fiction, this memoir reads lyrically. In this memoir, Roy opens up about almost everything that haunts her with utmost authenticity. It’s a raw, visceral and searing recollection of a life worth living—or a life worth having tried to live so far. Check out the full review of Mother Mary Comes to Me here.

For the last three months, after every morning run, I have been reading William Zinsser’s On Writing Well, a craft book on writing well in the English language. To write well, Zinsser tells us, one must focus on their voice. There is no such thing as an effortless style. So, read good books. And always imitate another writer. ‘Imitation is part of the creative process for anyone learning an art or a craft.’ So, find the best writers you can copy. Get their voice and taste in your ear, and very soon, your voice and your identity hone out of it. Enjoy the process of writing. If writing is all that you hope to do, then learn to enjoy it as well as you can. Listen to your editors. But learn to differentiate between good advice and bad advice. And experiment. Check out my notes on William Zinsser’s tips for writing well.

These are some of the books I had the chance to read, besides the usual set of texts and books one ought to read for their own PhD projects. I have two other Han Kang books lying on my desk, which I will begin reading in the next few days. There is Hideo Yokoyama’s The North Light. Additionally, there are some notable books by authors such as Rachel Cusk, Kiran Desai, and Oliver Sacks, among others, that are worth reading.

I also have a few philosophy and political theory texts, which I will read this year. One being J.S. Mill’s On Liberty. Another is Isaiah Berlin’s Four Essays on Liberty. Then, Peter Singer’s Practical Ethics. And then, Jostein Gardner’s Sophie’s World. And I hope, as the year passes by, there will be some books that come to my attention—and that I will read. So, I am excited for 2026. You, too, dear reader, feel free to write to me about the books I can read based on what I have read this year. For now, I stop here and get back to the usual PhD life.

With my kind regards,

Adarsh

Hi Adarsh,

Thanks for your post about the books you have read and thought and written about in the last year. There are some I have read and like as well. But are there some which you’ll read again and again. For me this is the test of the book as well my reading. Han Kang’s The Vegetarian is one of them. I have already read it twice and will read it again. I like her Greek Lessons and The White Book quite a lot. I read the books again not for the plot but for the language most of all and for the ideas and emotions. I apologise for this indulgence. You already know all this.

Let us keep reading and learning about the world but most importantly about ourselves. Read less books but read them more than once.

Subhash

Thinking Aloud