on Edward Said and writing, teaching sociology better, Jon Fosse, feminist killjoy, and writing good book reviews

a curated list of exceptional articles for your weekly intellectual curiosity

Dear Reader,

This is the third edition of fuzzy notes, a weekly newsletter on politics, philosophy, society, culture, and international affairs.

The week, for me personally, has been rewarding. Many things are happening in life—which I hope to share with you very soon. Apart from that, there have been many things happening on the international front.

Since yesterday, there has been a situation of continued escalation of Israel-Palestine relations, with Hamas in the Gaza Strip attacking parts of Israel. The week also has seen the Nobel prize given to people in various fields of research.

Back home in India, there was a police raid on a not-very well-known but often critical established regime, news media, Newsclick, in Delhi—another aspect of how institutional corrosion is evidenced in India on an ongoing basis. And there have been many more things. This week’s newsletter reflects all these aspects briefly.

Along with the excerpts of these articles, some complementary readings are also linked in the newsletter.

Politics: On Edward Said and Writing in the Service of Life

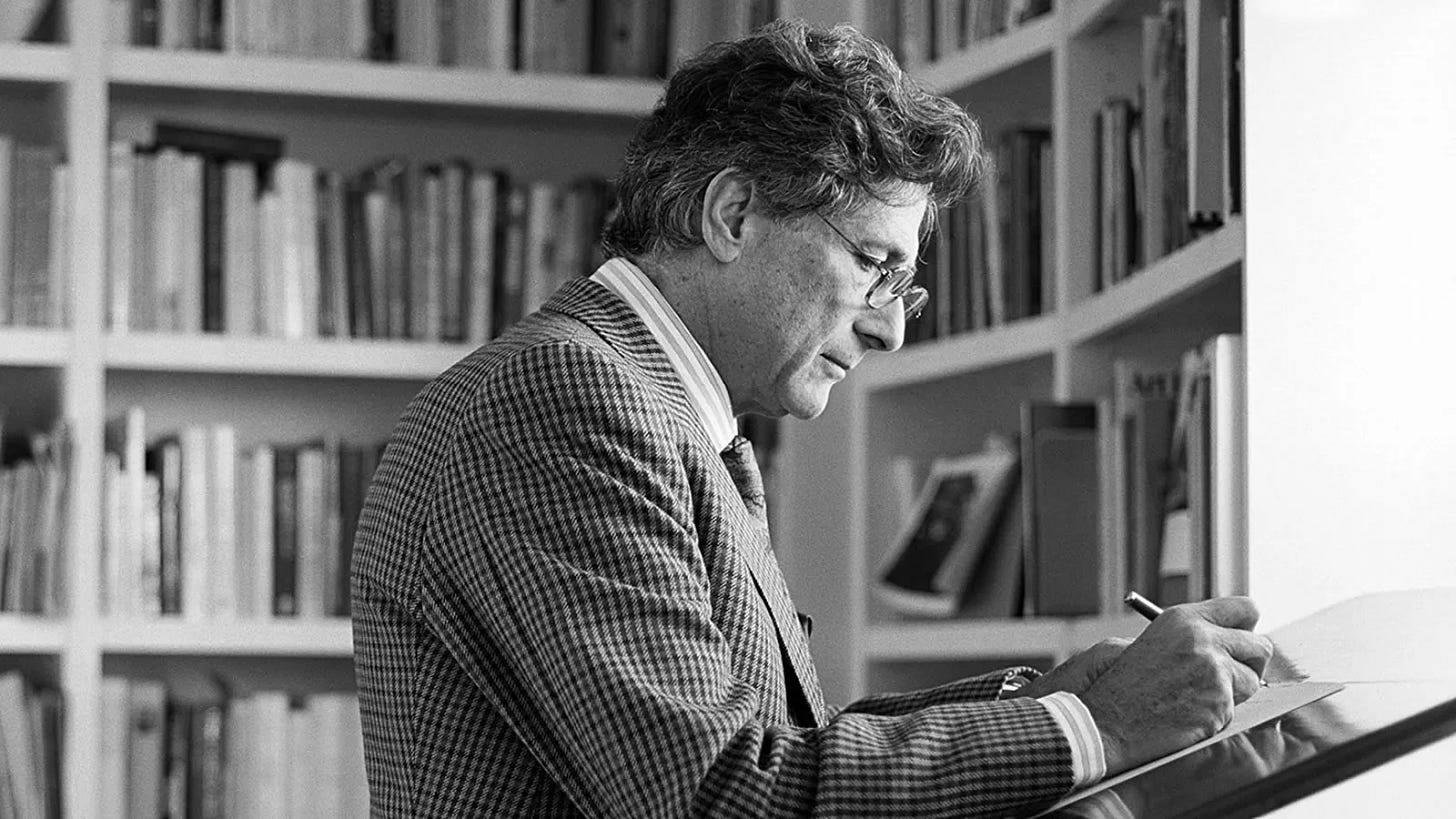

Not many in social sciences in the modern day have had a profound influence as Edward Said has had on the understanding of culture, society, and representations.

When I first read Said’s Orientalism as a master’s student at Delhi University, I enjoyed every paragraph of the first few chapters. I re-read it through and through over the period. Said has had a significant influence on those who study postcolonial theory.

This article by Layla AlAmmar, titled: “Edward Said: Writing in the Service of Life”, illustrates how Said’s life was that of service. An innate desire to see things change and their role in shaping those changes.

This is a brilliant essay on how Said’s life was one of the examples of how (we, students, writers, intellectuals, and philosophers) can truly write – in service of life.

It takes time for an idea like that to truly sink in, to think of truth itself as a representation that is constructed and circulated, received and consumed, or to conceive of it as something that travels far beyond its origins, that outlives the context which produced it. Consider the “great many other things” that are interwoven with representations: language, culture, history, political and religious leanings, all the known and unknown idiosyncrasies of the representer. These constructions don’t emerge from a vacuum, nor do they subsequently float in empty space. Rather, they inhabit what Orientalism determines to be “a common field of play [that has been] defined for them.” In his more charitable moments, Said conceives of representations (such as novels) as belonging to a family, existing in a kind of ecosystem of references and linkages. His thoughts on the nature of representation are some of his most insightful and had a profound effect on how I would conceive of my writings, both creative and scholarly, from that point on.

So gripped was I by Orientalism that I went on to read (and reread) nearly everything Said wrote — from Culture and Imperialism to Freud and the Non-European to Beginnings to his brilliant essay collection, Reflections on Exile. Immersing myself in his corpus showed me a few things, perhaps the most significant of which was that you cannot be content with an intellectual’s first utterance on a topic.

Complement reading on Edward Said with Tariq Ali on Edward Said; Tariq Ali’s interview of Edward Said; and if you haven’t read Edward Said, READ HIM!

Society: Teaching in a Trump Country: The Political Potential of Introductory Sociology

Sociology, if not appropriately taught, harbours a disconnect with reality. Many students of sociology face this intrinsic problem. When I read the sociological interventions on the caste system in India, I am dismayed by how little scholars have dealt with the complexities of it, how unfair their understandings are, and how ideologically driven their assessments are.

I have often told my peers how little sociologists know about Indian society – how focused they are on numbers and how little they conduct village studies—and understand the inherent logic of caste, class, gender, etc.

My dismay towards how understudied Indian society was pushed me towards my interest in politics. In the next essay titled: “Teaching in a Trump Country: The Political Potential of Introductory Sociology”, Shelly Steward addresses the logic of initial dismays students of sociology carry—and how one should deal with and address them.

As a Berkeley sociologist living in Williston, I found myself caught between two discourses—one held by the oil workers I spent my days with, another among fellow academic sociologists. Based on contributions to political campaigns, academics and oil and gas workers make up the most ideologically liberal and conservative professions. These differences run deep, and are rooted to the careers themselves. Many academics see freedom of speech and accessible education as central to their profession; oil workers see environmental deregulation and privatization as central to theirs. I heard these two discourses daily and struggled to draw any lines between them; each side seemed closed to the other.

Using everyday examples that seemed apolitical, though, allowed students to develop an understanding of society and their own relation to it. And that understanding held great political potential. For some students, it meant giving them a way to articulate the fear and discomfort they felt. For others, it meant coming to see the election as more than a distant news event or a one-issue matter. These lessons, students told me, helped them see why sociological thinking was relevant to them, and equipped them to think about politics as something more than posting campaign signs that matched their neighbors’. They began to see themselves as part of a wider society, and to place their own community in an increasingly divided nation.

Read the full essay, and if you are an academic, incorporate some of these insights into your own writings.

Culture: John Fosse’s Search for Peace

The Norwegian-novelist, Jon Fosse, is the winner of the 2023 Nobel Prize for Literature. Fosse writes, as those who have read him claim, infusing both hope and affection in his work. He examines the lives of ordinary people in their everydays—the complexities they deal with.

Fosse is praised for his seven-part novel Septology, a “slow prose” of how a painter named Asle grapples with the death of his wife, Ales. In this culture section, I have chosen the New Yorker interview of Jon Fosse with Merve Emre.

The word that comes to mind to describe all this—the light, the music, the sacred waters, the sacred garments—is “pilgrimage.” One rarely sees living writers treated with such reverence. “I am just a strange guy from the western part of Norway, from the rural part of Norway,” Fosse told me. He grew up a mixture of a communist and an anarchist, a “hippie” who loved playing the fiddle and reading in the countryside.

He enrolled at the University of Bergen, where he studied comparative literature and started writing in Nynorsk, the written standard specific to the rural regions of the west. His first novel, “Red, Black,” was published in 1983, followed throughout the next three decades by “Melancholy I” and “Melancholy II,” “Morning and Evening,” “Aliss at the Fire,” and “Trilogy.”

To read Fosse’s plays and novels is to enter into communion with a writer whose presence one feels all the more intensely owing to his air of reserve, his withdrawal. His plays, whose characters usually have generic names—the Man, the Woman, Mother, Child—seize upon the intensity of our primordial relations and are by turns bleak and comic.

I have not read Jon Fosse yet. But the kinds of articles I have read about his writings make me want to read him soon.

Philosophy: Feminist Killjoy Handbook with Sara Ahmed

I have read Sara Ahmed. She is a brilliant feminist writer who both allows you to feel and be touched by the subjects she engages with. I have learnt quite a lot from her writings—and I hope to write like her someday.

“Sara’s work both as a scholar in the academy working on queer phenomenology, on post-coloniality, and on emotions, as well as her work after she left the academy, has been an inspiration.” Here is a podcast of her interview with Academic Aunties (Ethel Tungohan). Listen in here.

International Affairs: What Makes a Good Book Review

This is not an article I read this week. However, as I thought through what to post for this week’s international affairs section, I thought of posting this brilliant essay on writing book reviews by Amanda Murdie.

I have quite learned from this essay about how writing a good book review works—and how one should write well. Despite all the resources that are out there on how one should write a book review in IR, I found this to be the most helpful essay.

This is one of the best and most exciting book reviews I have read in a long time in IR.

It is the end of this newsletter. I hope this reading list will keep you busy for the next week as you straddle between family, work, and leisure.

See you next week! Until then, happy reading :)